Post text here

Random thoughts on the day after #Indyref

Sitting in an Edinburgh restaurant nursing a second cappuccino and glass of wine. Trying earlier to eavesdrop unobtrusively on two Scottish gentlemen at a nearby table having ice cream and in sombre mood. A definite feeling of sadness. As an Irish friend of Scottish independence, I, like so many others, had hoped for an epic night of celebration last night, marking the dawn of a new polity in the family of nations, an ally and friend for Ireland in the context of these islands, Europe and the world. So much in common to unite us: a shared Gaelic linguistic heritage and millennia of historical influence through St Colm Cille (Columba), the kingdom of Dalriada and migration; centuries of common experience with England (a lot bad, a lot good, too); the kinship and creative tension and disturbance caused by the (largely) Scottish plantation of Ulster which gave Ireland its biggest Protestant denomination (and, paradoxically, had a big influence on Irish Republicanism); the contribution of Edinburgh-born James Connolly, socialist and 1916 leader to Irish independence – and so much, much more.

I came to Edinburgh only on Wednesday evening, the eve of polling. Yesterday morning, polling day, I showed up at the Yes Scotland office in Newington, south central Edinburgh, a short distance from my guesthouse on Minto Street. Offering to help for a few hours, I soon found myself visiting tenement dwellings in the Newington district guided by Edinbugh university student David Kelly, a pleasant young man, SNP member and student of politics. He showed me the ropes as we called on people in the lists supplied to us as potential Yes voters, climbing dark narrow steps in three-storey buildings, checking whether the occupants had voted yet, and trying to get the Yes vote out. These impressive terraces in the Livingstone Place, Mellview Drive and Moncrieff Terrace areas, featured late 18th/early 19th century town houses of the upper classes, which were sub-divided into small dwellings. These were now occupied by couples, some families and a transient population of students. Back later to the Yes office to report our findings for later follow-up. In the afternoon of polling day a shorter session, following up part of the earlier list with a South African-residing Scotsman, Ken, his car festooned with yes posters, which he parked strategically for maximum impact. And in the late evening, a final check on the remnants of a different list, with Jack Martin of the Radical Independence Party, driving in the evening darkness in his car around the more salubrious Grange Lodge and Grange Terrace districts. By then, most people had voted- the remainder probably weren’t going to vote.

I came to Edinburgh only on Wednesday evening, the eve of polling. Yesterday morning, polling day, I showed up at the Yes Scotland office in Newington, south central Edinburgh, a short distance from my guesthouse on Minto Street. Offering to help for a few hours, I soon found myself visiting tenement dwellings in the Newington district guided by Edinbugh university student David Kelly, a pleasant young man, SNP member and student of politics. He showed me the ropes as we called on people in the lists supplied to us as potential Yes voters, climbing dark narrow steps in three-storey buildings, checking whether the occupants had voted yet, and trying to get the Yes vote out. These impressive terraces in the Livingstone Place, Mellview Drive and Moncrieff Terrace areas, featured late 18th/early 19th century town houses of the upper classes, which were sub-divided into small dwellings. These were now occupied by couples, some families and a transient population of students. Back later to the Yes office to report our findings for later follow-up. In the afternoon of polling day a shorter session, following up part of the earlier list with a South African-residing Scotsman, Ken, his car festooned with yes posters, which he parked strategically for maximum impact. And in the late evening, a final check on the remnants of a different list, with Jack Martin of the Radical Independence Party, driving in the evening darkness in his car around the more salubrious Grange Lodge and Grange Terrace districts. By then, most people had voted- the remainder probably weren’t going to vote.

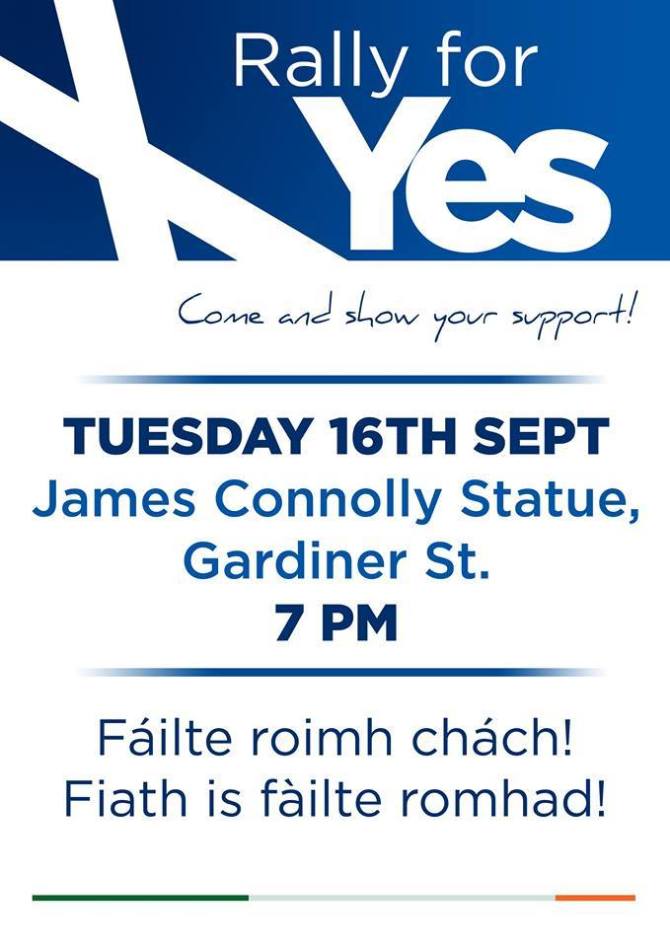

It was an exhilarating experience of activism which I hadn’t had since my student days in College in the 1980s, and I remembered popular culture on the radio in that era when politics had felt grittier, less subject to spin; the music of the Specials, UB40, the Style Council combining protests at Thatcherite materialism with chutzpah, sassy lyrics and an infectious beat. Just last Tuesday night, it had been a great experience to be in the company of other politically-engaged and enthusiastic people such as Trinity students Féilim MacRóibín and Jeff Johnston and others who mounted a display at the James Connolly statue in Dublin’s Beresford Place. This was a small gesture of support to the Yes campaign from an Ireland which (with a number of honourable exceptions such as journalists Colm Ó Broin and Concubhar Ó Liatháin, Irish language activist Caoimhín Ó Cadhla, economist David McWilliams and historian Diarmuid Ferriter) had largely slept through the two-years long debate, awakening only at the penultimate stage with low-level derivative commentary. We, a nation which had to fight a long and difficult campaign to secure our own independence, could and should have done more to offer an imaginative encouragement and support to our Scottish friends who were presented with a unique and almost unparalleled chance to secure it in a peaceful ballot. But like its metropolitan Westminster counterpart, who seem to represent the “gold standard” to which so many of our Irish journalists aspire, the Irish media class enjoys its comfortable ensconcement in the Kildare Street bubble, talking to each other, often conveying a dreary uniformity (even in criticisms of aspects of politics), and with little sense of an Ireland beyond the confines of the metropolis. Who can’t understand that loving Scotland and wishing it to join the community of nations in its own right does not mean- and never meant- hating England. Like Irish academia, it had little or nothing to offer Scotland in solidarity.

Where does all that grassroots energy and engagement tapped by the #YesScotland campaign go now? As an outsider, a few humble ideas occur, inspired by a few things I observed. On the voter-drive yesterday, Ken (the Scot home from South Africa) suggested the SNP should rebrand as Yes Scotland. But perhaps it should go beyond that, create a larger umbrella under that name, encompassing the Green Party and other non-SNP elements. Hugely impressive though he is, Alex Salmond (and nobody else could have brought matters this far) and the SNP are not universally liked, even on the Yes side (though the ugly caricatures by elements of the No campaign say more about it than they do about him). Progressives need to sustain the unique sense of national purpose and energy now existing through festivals, events and political discussion groups along Ireland’s Leviathan model, in every town in Scotland. Keep the grassroots engaged and keep that title which embodies positivity and hope. Create a fresh and inclusive social media platform building on disparate organisations such as YesLGBT, the Labour activists and members, the Greens, Women for Independence, student groups etc, which fused so many elements of society into a broad popular campaign that came within touching distance of history. And for all Ireland’s failure in this debate, take a lesson from our history. Take every inch of the devo-max settlement (when it comes, and come it must), and work it to the full. As deValera did with the Collins settlement he had eschewed in 1922. Keep the international engagement with a Scottish bureau in major international centres- all that is needed is an office, a PC an internet connection and people with a few hours to spare. Keep the international friends of independence engaged with Scotland’s development through contact and information, and show the world that the triumph of No did not mean the end of Yes. The world’s attention will move on, now that the bright light that flashed briefly on the world stage has dimmed again. But it is not the end of the dream. And Yes Scotland’s friends abroad still care.

Should NI21 organise in the Republic of Ireland?

The website of Open Unionism recently featured an article by Dr John Coulter, who suggested the new unionist party NI21 should “strike out South”, arguing that

“If NI21 is not to join other moderate parties such as the Unionist Party of Northern Ireland and the Irish Nationalist Party in the dustbin of history, it must re-brand itself as an all-island movement.” Dr Coulter states “I have made no secret during my journalistic career of wanting to see Unionism expand beyond the boundaries of Northern Ireland into the South.”

In a response to this article, again kindly hosted by Open Unionism, I argue that Dr Coulter completely fails to take the wishes of his fellow catholic and nationalist citizens north or south into account. Southern voters have no desire to surrender their separate army, diplomatic service and EU and UN seats for the dubious benefits of a latter-day “Home Rule”. My response in full may be read here.

C of I Archbishop treads carefully at Arbour Hill

As a postscript to last October’s post on Church of Ireland responses to the 1916 Rising in the Jubilee Year of 1966, it was interesting to note that this year, May 2013, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin Dr Jackson was the invited preacher at the commemorative Mass in the Church of the Sacred Heart in Arbour Hill (home to the chaplaincy of the Defence Forces).This was the first time a Church of Ireland Archbishop delivered an address at the annual event which was attended by President Michael D Higgins, Taoiseach Enda Kenny and a number of Government ministers.

This writer was present in the church, and it was notable that the Archbishop did not refer directly once to the Rising or its leaders- in terms either positive or, which would hardly have been politic given the occasion, negative. This formed a strong contrast with Irish Anglican bishops’ sermons in 1966. Perhaps he was treading carefully. The only new ground broken was the fact of the invitation to preach itself. Maybe there will be something more concrete said in three years’ time, on the actual centenary.

The service was followed by a ceremony at the graveside of the 1916 leaders during which representatives of a number of different faiths read prayers.

Here is a link to the Archbishop’s address, on the Dublin diocesan website.

And here is a link to an interesting opinion piece on the day’s events by Tom McGurk, published in the Daily Mail.

Pursuing Inclusivity: C of I responses in 1966 to the Easter Rising

This article appears in the Autumn 2012 issue of Search, a Church of Ireland journal. See further details below.

In 1966, the Government in the Republic prepared elaborate plans to mark the Golden Jubilee of the 1916 Easter Rising. The Commemoration Committee’s programme was announced by Taoiseach Seán Lemass on February 11th, and featured religious ceremonies, military, public and children’s parades, the opening of the Garden of Remembrance, the unveiling of the Thomas Davis statue in College Green, Dublin, a pageant at Croke Park and numerous other cultural events. There was a determined effort to include all sections of southern society and the official programme set the agenda for local initiatives. On Easter Monday, there would be religious ceremonies throughout Ireland, including Solemn Votive Masses, ” Church of Ireland services and special prayers in Diocesan Cathedrals”.[1]

In the South, the Church of Ireland, notwithstanding the distinguished role a number of its sons and daughters had played in the national revolution[2], was still associated in the minds of many with the ancien régime which it had sought to supplant, and with remembrance of the Great War. Conscious of this, she was anxious to lend her cooperation to this national commemoration.

Being an all-island church, there were certain tensions. Perhaps with an eye to the IRA border campaign of the 1950s, an article was published in the Church of Ireland Gazette entitled “A Time to be ‘the Church of Ireland’ ”. It sounded a warning note in relation to the upcoming celebrations, stressing the necessity to ensure that no action should be contemplated which could be interpreted as a aligning the church with one side or the other.

It set out starkly the conflicting views on the rebellion. Easter 1916 represented “the very vortex of the disagreements of the Irish people. To some it is the epitome of glory, and to others, of shame…. For some the smoke of burning was the veil of a terrible beauty, for others the mark of the funeral pyre of a nation’s honour. ….In the context of the Church of Ireland, it must be added, with heavy emphasis, that this irreconcilable conflict exists even within her own ranks and the line of it does not conform to that of the political border”. It concluded by saying that “even without the possibility of irritant being provided by an illegal organisation, there are here all the makings of trouble, and it behoves us… to look the situation in the eye and rally the forces of goodwill and common sense.” [3]

“The Rector would like it made known that the Church of Ireland is not indifferent to the jubilee commemoration of Easter Week, 1916 ,” ran a report in the Connaught Telegraph [4]. In Nenagh, the rector sent apologies to a commemorative planning meeting, explaining “we feel that Easter Day itself, celebrating as it does the Resurrection of our Lord, is so fundamentally important that we cannot alter the liturgy for that day. However, we are holding on Easter Monday a diocesan service in the Cathedral at Killaloe at 11am, to be attended by all clergy and people and at which the Bishop will preach a special sermon.”[5]

Church of Ireland services appeared in commemorative programmes in such places as Cloughjordan, Co Tipperary; Killarney; Tralee; at the Cathedral of St John the Baptist and Saint Mary in Sligo, and in Drumshanbo.

The Connacht Tribune, reporting on a service in Kilmacduagh Group of Parishes, noted that special prayers were authorised for use by the House of Bishops, including the following bidding: “Beloved in Christ, we are come together in the presence of Almighty God to offer our worship to him in thanksgiving and prayer. Let us give thanks to Him this day, the 50th anniversary of the proclamation of our country as a sovereign independent state, and remember with thanksgiving before Him, the courage and devotion of those who pledged their lives and the lives of their comrades in the cause of freedom and welfare of this nation…. “ [6]

Many northern members of the Church looked with dismay at her participation in the southern commemorations. A commemorative service was held at St Eunan’s Cathedral in East Donegal[7] (presided over by the Bishop of Derry and Raphoe, Dr Tyndal, whose diocese straddles the border). However, a resolution expressing “consternation and regret” that some Church of Ireland churches intended to hold such commemorative services was passed by the Select Vestry of Glendermott Parish Church, across the border in County Derry. A copy of the resolution was to be sent to the Diocesan Council with a request that the bishops of the church direct that no such commemoration should be held in any of the churches in their diocese.[8]

The apex of the celebrations, Easter Monday, 11 April 1966, saw a heavy schedule of events in Dublin city. These included High Mass at the Pro-Cathedral at 10am, and a 1916 Commemoration service from St Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin at 11am. The formal opening of the Garden of Remembrance at Parnell Square, Dublin was scheduled for 11:55am.

The event at St Patrick’s was a United Service organised by the Dublin Council of Churches. In an unauthorised action prior to this service, a wreath was laid on a War Memorial in the Cathedral by Major R Bunting of Dundonald, Belfast “in memory of the British officers who died in the line of duty in Dublin in Easter, 1916.”[9]

In his sermon, Archbishop George Otto Simms noted that the service included Thanksgiving and Commemoration, but also, as we faced the days ahead, Dedication.“The prayers we have used in our worship have been for our country, our President, and for all those who bear responsibility in government, administration, in our public and civic life. Their phrases and aspirations are very familiar, for we have used them regularly and constantly all through the years of the State’s progress and development. Today these prayers spring to life in a vivid way and emphasise with a fresh realism that our own way of life is not a mere private, self-interested pursuit, but something more like a call to use our energies, activities and gifts, such as they are, for the general good and for the life together that we share in country and community.

Dr Simms had words of praise for the efforts of the State to foster tolerance since independence: “There is much for which to give thanks on our commemorative occasion. We are grateful across the span of the last 50 years for the goodwill, tolerance and freedom expressed and upheld among and between those of differing outlooks and religious allegiances. The words of the Proclamation that guarantee ‘religious and civil liberty, equal rights and opportunities to all citizens’ have brought help and encouragement to minorities during this period. There is a rock like quality about such elements in the formation of a State”.

He noted the voice Ireland had in world councils as a result of the sovereignty won: “We give thanks, too, for the spirit of reconciliation and goodwill that has been evident in recent times. Understandably, our prayers are offered for the peace of the whole world in which we are set as a country with a place and a voice in international assemblies. “Our country’s place in the world of nations, not least in the councils that are concerned with world peace and harmony among all men, has been a notable one as a result of the vision of our statesmen..”[10]

Rather embarrassingly, Archbishop Simms was locked out of the opening ceremony at the Garden of Remembrance, which was being performed by President de Valera, and featuring a blessing by Archbishop McQuaid. Dr Simms had been collected in a State car from St Patrick’s and was accompanied by the Rev William McDowell, representing the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, and Councilor Maurice Dockrell TD. When they arrived at the Garden, the gates had already been shut for the ceremonies and officials were unable to find a key to open them. A key eventually was found, but at that stage the ceremonies were nearly at an end.[11] The President in his remarks expressed thanks to both Archbishops McQuaid and Simms for the services held that day.

Another service was held in Cork, presided over by the Bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, the Right Rev Dr RG Perdue: “Let us look to the future with hope and optimism. “The idealism, sincerity and determination of the 1916 leaders was a challenge to us, both as citizens and Christians.” The Proclamation itself, written and read at a time when there was much tension and feelings were running high, was a tribute to the leaders’ vision, charity and breadth of vision. What stood out about 1916 was the courage of that little band of men who, for their ideals, were prepared to risk all and sacrifice all, even life itself. “Men of such calibre must be held in the esteem of friend and foe alike. They set a standard of service admired by all and they are a challenge to all complacency.” Warning that it was the duty of citizens to take a full part in the life of the community, he said that where there was injustice, “our voices should be heard so that we inform public opinion, which, in turn, can have a powerful influence on the direction of policy.”If we are as dedicated to the spread of Christian love and to the expression of the Will of God in human affairs, as the men we remember today were dedicated to the cause of Ireland, we, too, could shake the nation and accomplish ends greater than our wildest dreams.”[12]

The Right Rev Dr Wyse Jackson, Bishop of Limerick, Ardfert and Aghadoe preached at a special service in St Mary’s Cathedral, attended by the Mayor and members of the Corporation. At Killaloe, a service of intercession for Ireland was held in Saint Flannan’s Cathedral. The Bishop, the Rt Rev HA Stanistreet, preached, referring to the “genuine idealism in 1916”. “There has been little or no corruption in the machinery of the Republic. Not one of our public men has had his name besmirched by scandal.” Noting that members of the church had served the Republic in Dáil, Senate and judiciary, he said “God will judge us by what we strive to be and to do. We as Irish Church people must affirm our loyalty to the State.”[13]

A day of ceremonies focussed on schoolchildren was held throughout the State on Friday, 22 April 1966. In its report “Schoolchildren Pay Tribute to Men of 1916”, the Irish Press reported that “at special Masses and Church of Ireland and Jewish services, they prayed for those who lost their lives in the Rising. In the schools they recited the Proclamation and sang the National Anthem.” Some 2,000 children from Church of Ireland, Presbyterian and Methodist schools in the city attended a ceremony at St Patrick’s Cathedral Dublin, where they were told by the Archbishop, Dr Simms, that they were right to meet for worship to dedicate themselves to the service of their country: “We dedicate ourselves today to the kind of service that will be rock-like in laying foundations of a life of truth and honesty both in private and in public; of charitableness in outlook and attitude with understanding that hears the other side in a human story or in any argument.” The Archbishop later unveiled a copy of the Proclamation in St Patrick’s Cathedral Grammar school.[14]

These actions were mirrored in other places. In Co Meath, there were commemorations in the Carrick and Westland schools (featuring a reading of the Proclamation , the National Anthem and the placing of a commemorative plaque), and services at Preston and Flower Hill schools.[15] At Midleton College’s celebrations in County Cork, the Headmaster, Mr JW Smyth urged the boys to dedicate themselves anew to their country, so that when the centenary celebrations of the Rising came about they would feel a far greater pride and justification in their achievements than the present generation felt today. [16]

On Monday 25th April, the Irish Independent reported on another gesture- Archbishop Simms handing over to the Lord Mayor of Dublin of the site of the Wolfe Tone Memorial Park in the grounds adjoining Saint Mary’s Church, Mary St, Dublin, on behalf of the Church of Ireland Representative Body.

The Church of Ireland’s southern leadership, and in particular Archbishop Simms, were responding to the prevailing view of 1916 in southern society at the time. The press reports indicate nonetheless a nuanced understanding and greater acceptance of the complex conditions surrounding the birth of the independent state on the part of much of the Church than might sometimes be projected back by contemporary stereotypes. Through its involvement in the celebrations, the philosophy and process of constructive engagement with the State heralded through the pamphlets of WB Stanford (A Recognised Church, 1944) and HR McAdoo (No New Church, 1945) were being continued and deepened.

It must also be recalled that, notwithstanding the north-south rapprochement with the Lemass/O’Neill meeting, the two parts of the partitioned island remained largely unknown to each other. Paisleyite elements excoriated the Church of Ireland’s role in the southern celebrations. Official recognition in the South of the service of Irish men and women in the world wars was still largely absent. “Revisionist” critical studies of the Rising would only gain ground with Father Shaw’s article[17], published in Studies in 1972. Despite occasional episodes of violence in Northern Ireland, the long conflict as we have known it was yet to develop.

The Troubles, which began in 1969, frightened the establishment in the South, who wanted to avoid “giving succour” to paramilitary groups claiming to be the inheritors of the 1916 vision. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, substantial commemoration of 1916 was discontinued, and indeed actively discouraged, in the Republic. It was not until the 1994 ceasefire and the Peace Process (culminating in the Good Friday Agreement) that there would be any significant relaxation in this regard. In late 2005, Taoiseach Bertie Ahern announced that his Government would revive the annual military ceremonial at the GPO. Amid hostility from certain quarters in the media, a military parade went ahead, 120,000 people lining the streets of Dublin. The Irish Times declared in its headline that Ahern’s parade “had won political approval”.

In 2011, Queen Elizabeth laid a wreath in the Garden of Remembrance in memory of those who had fought for Irish freedom (and at Islandbridge in memory of those Irish who had served with the British Army in the Wars). The southern state had finally moved in recent times to acknowledge the many thousands of Irish who fought and died in the First and Second World Wars. Television documentaries and books brought their sacrifice to the attention of the public. Of course, the Church of Ireland continued always to remember her War dead at annual Remembrance Day ceremonies. But in 2012, Archbishop of Dublin Michael Jackson also participated in an interfaith prayer service at the State’s 1916 commemoration in Arbour Hill – a higher level of Church of Ireland representation than had been seen at 1916 Rising ceremonies for quite some time.

- Archbishop Jackson at the interfaith service during the 1916 Commemoration at Arbour Hill, May 2012

___________________

NOTES

[1] Irish Press, 12th of February, 1966

[2] See article Harry Nicholls & Kathleen Emerson: Protestant Rebels by Martin Maguire, 35 Studia Hibernica, 2008-2009

[3] Irish Press, 5th February, 1966

[4] 5th May 1966

[5] Nenagh Guardian, 5th March, 1966

[6] Connacht Tribune, 16th April, 1966

[7] Irish Independent, 4th April 1966

[8] Ibid.

[9] Irish Times, 12th April, 1966

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Nenagh Guardian, 16th April, 1966

[14] Irish Press, 23rd April, 1966

[15] Meath Chronicle, June 11, 1966

[16] Southern Star, 30th of April, 1966

[17] “The Canon of Irish History, A challenge” by Father Francis Shaw SJ, Studies, 1972

Note: This article appears in the Autumn 2012 issue of Search, a Church of Ireland journal. It is one of a trio of articles relating to the Decade of Centenary commemorations of events ranging from the Ulster Covenant in 1912, the Great War, the Easter Rising, the War of Independence etc. The other articles in this trio feature an overview by Bishop John McDowell of Clogher, chairman of the Church of Ireland working group on the centenaries, and a piece by Wilfred Baker, diocesan secretary in Cork, offering a southern unionist perspective. The current issue also features articles on the debates on sexuality currently animating the Church of Ireland.

Symposium on Official Languages Act 2003 in TCD- 21 January 2012

The School of Law and the Irish Language Office, Trinity College Dublin, in Association with the Four Courts branch of Conradh na Gaeilge (and with the support of Guth na Gaeltachta) are holding a Public Symposium on the Official Languages Act 2003 in Trinity College on Saturday, 21 January 2012.

“Acht na dTeangacha Oifigiula: Leasú Chun Feabhais” (the Official Languages Act 2003: Increasing Its Effectiveness) will be the title of this symposium, which is being held in the context of the review recently announced by the Government of the operation of the legislation, and its effectiveness.

This symposium will be comprised of three separate elements:

- SESSION 1 (10.00-11:45 AM): a Review of the Implementation of this Legislation since 2003, with speeches from the Official Languages Commissioner, Seán Ó Cuirreáin in relation to the experience of his own office; from a representative of the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht; and a perspective from an Irish Language Officer in a public body, in relation to how the legislation operates internally in an public body.

- SESSION 2 (12.00-1:30 PM): Perspectives on the Effectiveness of the Legislation, with contributions from a legal practitioner (Dáithí MacCárthaigh BL) in relation to how the legislation operates in the legal system; from Julian deSpáinn, General Secretary of Conradh na Gaeilge, on the views of Irish language organisations on the effectiveness of the legislation and their proposals for its improvement; and from Éamonn MacNiallais from the community campaigning group Guth na Gaeltachta on experience of how of the legislation serves language rights on the ground in the Gaeltachtaí, and the improvements which they feel are necessary.

- SESSION 3 (2.00-3:00 PM): Open Discussion Forum- Differing Perspectives on the Legislation in the context of the Review, with Irish language organisations and individuals. Emer Ní Chonaola, (TG4) will chair this discussion forum. Ms Ní Chonaola is the anchor news presenter on TG4. Originally from Spiddal, she is a graduate of the National University of Ireland, Galway.

It is the objective of this symposium to compile a comprehensive Paper, based on the day’s proceedings, on the range of issues which must be taken into consideration in the Governmental Review. This will be achieved through retaining a rapporteur, who will closely follow the proceedings of the day and will prepare the Paper, which will then be submitted to Government for consideration as part of its review process.

This event will be open to students, legal practitioners and the Irish language community, as well as representatives from Irish language organisations and others with an interest in the topic, and all viewpoints will be particularly welcome in the discussion forum.

Refreshments will be available. The day’s proceedings will commence at 10.00am with a welcome from Professor Gerry Whyte of the School of Law, Trinity College, and a few words from Eithne Reid O’Doherty BL, chairperson of the Four Courts branch of Conradh na Gaeilge.

DETAILS OF SPEAKERS

Seán Ó Cuirreáin

Seán Ó Cuirreáin was appointed on 23 February 2004 as the first Official Languages Commissioner, under the Official Languages Act 2003. He was reappointed for a further six year term on 23 February, 2010. The role and powers of the Language Commissioner are set out in the Act, and he enjoys complete independence in his role as Commissioner.

Aonghus Dwane

Aonghus Dwane is Irish language officer in Trinity College, which introduced its Irish Language Scheme in 2010, and is also a solicitor, who worked on the DPP’s Irish Language Scheme during his time in that office.

Dáithí MacCárthaigh BL

Dáithí MacCárthaigh is a barrister. He is also coordinator of the Law and Irish programme at the King’s Inns. He lives in the Rath Cairn Gaeltacht.

Julian de Spáinn

Julian de Spáinn is General Secretary of Conradh na Gaeilge since 2005, and before that was manager of Seachtain na Gaeilge Teo. He was President of the Union of Students in Ireland in 2000/01.

Éamonn MacNiallais

Éamonn Mac Niallais is the spokesperson for Guth na Gaeltachta (a non-party political campaigning group focussed on the Irish language and the Gaeltachtaí). He is also the Administrator of the Gweedore Centre of Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge.

Further information is available from the following contact persons:

- Aonghus Dwane, Irish Language Officer TCD. gaeloifig@tcd.ie Tel; +353 (0)1 896 3652, 087 6232841

- Eithne O’Doherty BL, Four Courts Branch, Conradh na Gaeilge eodoherty@lawlibrary.ie, Tel 086 8 380 380

- Síne Nic an Ailí, Feidhmeannach Forbartha & Oifige, Conradh na Gaeilge sine@cnag.ie, Teil +353 (0)1 4757401, 087 6546673

Queen Elizabeth II views first printed Irish book in Trinity College

On her visit to Trinity College Dublin during her recent State Visit to Ireland, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was shown by Robin Adams, Librarian, the first book ever printed in Irish in Ireland. This was an Irish Alphabet and Catechism- Aibidil Gaoidheilge 7 Caiticiosma– which was printed by John Kearney with type presented by Queen Elizabeth I in 1571.

William Bedell (1571 to 1642), a Provost of Trinity College Dublin, and later Bishop of Kilmore, had the Old Testament translated into Irish. This was printed in London in 1685, together with a translation by William Daniel (died 1628) of the New Testament- Tiomna Nuadh. The completed work became known as “Bedell’s Bible”. Daniel, who became Archbishop of Tuam in 1609, also translated the Book of Common Prayer into Irish. Leabhar na nUrnaithe gComhchoiteann was printed by John Francke in 1608.

A number of later editions of the Book of Common Prayer were also translated into Irish. When Bedell was Provost of Trinity College, those from a Gaelic background who were studying for the ministry were obliged to attend lectures in Irish in order to evangelise the Gaelic-speaking population.

We saw a Vision- poem to be read at Garden of Remembrance

The text, in English and in Irish, of the poem that will be read today at the Garden of Remembrance in the presence of her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, who will lay a wreath in memory of those who died in the struggle for Irish freedom.

We Saw A Vision

In the darkness of despair we saw a vision, We lit the light of hope, And it was not extinguished, In the desert of discouragement we saw a vision, We planted the tree of valour, And it blossomed

In the winter of bondage we saw a vision, We melted the snow of lethargy, And the river of resurrection flowed from it.

We sent our vision aswim like a swan on the river, The vision became a reality, Winter became summer, Bondage became freedom, And this we left to you as your inheritance.

O generation of freedom remember us, The generation of the vision.

“As Gaeilge” For those who can understand, the poem is much more powerful in its native language. As Gaeilge, it goes like this:

I ndorchacht an éadóchais rinneadh aisling dúinn. Lasamar solas an dóchais. Agus níor múchadh é.

I bhfásach an lagmhisnigh rinneadh aisling dúinn. Chuireamar crann na crógachta. Agus tháing bláth air.

I ngeimhreadh na daoirse rinneadh aisling dúinn. Mheileamar sneachta táimhe. Agus rith abhainn na hathbheochana as.

Chuireamar ár n-aisling ag snámh mar eala ar an abhainn. Rinneadh fírinne den aisling. Rinneadh samhradh den gheimhreadh. Rinneadh saoirse den daoirse. Agus d’fhágamar agaibhse mar oidhreacht í.

A ghlúnta na saoirse cuimhnígí orainne, glúnta na haislinge…

Liam Mac Uistín

A citizen’s welcome to Her Majesty

Note: this article comments primarily on the wreath laying ceremony to take place in the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin as part of the State Visit of Queen Elizabeth to Ireland, as this is the aspect that has been given little prominence in commentary to date.

Note: this article comments primarily on the wreath laying ceremony to take place in the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin as part of the State Visit of Queen Elizabeth to Ireland, as this is the aspect that has been given little prominence in commentary to date.

As a citizen of the Republic of Ireland, I warmly welcome the visit of Queen Elizabeth II as Head of State of the United Kingdom, a dynamic cosmopolitan and multicultural state with whose people we enjoy warm and friendly relationships, whose vibrant and exciting capital London we love to visit. The Queen comes here in a different capacity to any of her predecessors who visited-she comes as an equal of any citizen in this state. As we are not her subjects, no bobbing or curtsying is necessary or appropriate (note to Pat Kenny, whose radio show on RTE radio one today featured an extended piece on the precise etiquette of greeting royalty, including advice to the public on the appropriate table manners). See here for a note on the appropriate etiquette, including advice to those who are not subjects.

The hope is that the Queen and her husband Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, will enjoy a warm welcome and a very pleasant stay here. The regrettable aspects are that she will fly into a virtual cordon sanitaire, a country in virtual lockdown, with most of the citizenry kept out of her view, because of a security threat from dissident republican elements such as the Real IRA, which enjoy virtually no community support in the North. The hope must be that, in carrying out their legitimate and necessary duties to safeguard the visiting dignitaries, the Gardaí will avoid heavy handed tactics with members of the public who come to view the spectacle, or with protesters who have an entirely legitimate right in a democratic society to register peacefully their opposition to this visit. All citizens should be aware of their rights, some of which are outlined here

The hope is that the Queen and her husband Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, will enjoy a warm welcome and a very pleasant stay here. The regrettable aspects are that she will fly into a virtual cordon sanitaire, a country in virtual lockdown, with most of the citizenry kept out of her view, because of a security threat from dissident republican elements such as the Real IRA, which enjoy virtually no community support in the North. The hope must be that, in carrying out their legitimate and necessary duties to safeguard the visiting dignitaries, the Gardaí will avoid heavy handed tactics with members of the public who come to view the spectacle, or with protesters who have an entirely legitimate right in a democratic society to register peacefully their opposition to this visit. All citizens should be aware of their rights, some of which are outlined here

Her Majesty will lay a wreath at the Garden of Remembrance near Parnell Square at the top of O’Connell Street. This park was formally opened in 1966, during the jubilee celebrations of the 1916 Easter rising, to commemorate all of those who fought in the struggle for Irish freedom which led to the foundation of the sovereign state in the 26 counties. The Queen will thus be acknowledging, on behalf of the United Kingdom, people like the poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary Patrick Pearse and the socialist and thinker James Connolly, as well as acknowledging the foundation of the State.

Her Majesty will lay a wreath at the Garden of Remembrance near Parnell Square at the top of O’Connell Street. This park was formally opened in 1966, during the jubilee celebrations of the 1916 Easter rising, to commemorate all of those who fought in the struggle for Irish freedom which led to the foundation of the sovereign state in the 26 counties. The Queen will thus be acknowledging, on behalf of the United Kingdom, people like the poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary Patrick Pearse and the socialist and thinker James Connolly, as well as acknowledging the foundation of the State.

It is a singular pity that some media commentators on this visit could not resist the opportunity to denigrate those who took part in the struggle for independence or to caricature the entire independent history of the state as a tale of emigration, censorship, priest-domination, poverty and linguistic compulsion. It has failed to factor in the good with the bad, or to set the first faltering steps of the new state, or its early ethos, in any appropriate historical context.

Pearse, who proclaimed a republic outside the GPO on Easter Monday 1916, and was executed some weeks later in the stonebraker’s yard in Kilmainham Gaol, once wrote:

For this I have heard in my heart, that a man shall scatter, not hoard,

For this I have heard in my heart, that a man shall scatter, not hoard,

Shall do the deed of to-day, nor take thought of to-morrow’s teen,

Shall not bargain or huxter with God ; or was it a jest of Christ’s

And is this my sin before men, to have taken Him at His word?

The lawyers have sat in council, the men with the keen, long faces,

And said, `This man is a fool,’ and others have said, `He blasphemeth;’

And the wise have pitied the fool that hath striven to give a life

In the world of time and space among the bulks of actual things,

To a dream that was dreamed in the heart, and that only the heart could hold.

O wise men, riddle me this: what if the dream come true?

What if the dream come true? and if millions unborn shall dwell

In the house that I shaped in my heart, the noble house of my thought?

Lord, I have staked my soul, I have staked the lives of my kin

On the truth of Thy dreadful word. Do not remember my failures,

But remember this my faith

On the wall of the Garden of Remembrance is inscribed the following:

We Saw A Vision

In the darkness of despair we saw a vision,

We lit the light of hope,

And it was not extinguished,

In the desert of discouragement we saw a vision,

We planted the tree of valour,

And it blossomed

In the winter of bondage we saw a vision,

We melted the snow of lethargy,

And the river of resurrection flowed from it.

And the river of resurrection flowed from it.

We sent our vision aswim like a swan on the river,

The vision became a reality,

Winter became summer,

Bondage became freedom,

And this we left to you as your inheritance.

O generation of freedom remember us,

The generation of the vision.

I salute the brave and visionary men who led the 1916 rising, those who fought and gave their lives for Irish independence, and remember with gratitude their sacrifice. I acknowledge the generosity of the Queen (and the British Government) in laying a wreath to the memory of these men on behalf of of her people, in so doing, acknowledging that they were inspired by the highest ideals, even if ones she would not share. It is very much to be hoped that unionists and dissenters will finally be moved to acknowledge that the men of 1916 were sincerely motivated, if their monarch can do so. Former Taoiseach Brian Cowen called in May of last year for Unionists to acknowledge the Easter Rising of 1916, in reciprocation for nationalists acknowledging the Battle of the Somme and the sacrifices of the First World War– see here for a report on this call, which has to date fallen on deaf ears.

I also salute those other Irish who fought and died for different ideals, and in the regiments of other armies. The Queen will also, quite rightly, lay a wreath to the memory of these men at the War Memorial Gardens in Islandbridge.

It seems that quite a significant speech will be made by the Queen at the state dinner in honour in Dublin Castle on Wednesday evening (this will be broadcast live on RTE 1 television). The presence of British Prime Minister David Cameron here is also a significant portent. Perhaps some progress will be made on the British side in releasing the files on the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, the atrocity which resulted in the greatest loss of life on a single day during the period of the Northern Ireland troubles.

May the State visit pass safely and well, and a new and hopeful epoch commence in relationships between these islands.

Commemorating 1916

Today I went along to the GPO in Dublin’s O’Connell Street to attend the official (state) commemoration of the 1916 Easter Rising. I posted a Facebook status update saying I was attending the event, and a friend posted in reply (in Irish): “seo an chéad uair a chuala mé faoi” (“this is the first I heard of it”). This was unsurprising, as the event was only publicised, in a fairly low-key way, in the past couple of days by the Department of Defence. Last year, when something similar happened, approximately 7,000 people assembled nonetheless in O’Connell Street. The media reported this and a columnist later wrote that this demonstrated that such commemorations had no popular support.

Today I went along to the GPO in Dublin’s O’Connell Street to attend the official (state) commemoration of the 1916 Easter Rising. I posted a Facebook status update saying I was attending the event, and a friend posted in reply (in Irish): “seo an chéad uair a chuala mé faoi” (“this is the first I heard of it”). This was unsurprising, as the event was only publicised, in a fairly low-key way, in the past couple of days by the Department of Defence. Last year, when something similar happened, approximately 7,000 people assembled nonetheless in O’Connell Street. The media reported this and a columnist later wrote that this demonstrated that such commemorations had no popular support.

Why did I go? Well, I have always thought that the group of men who led the Rising included some exceptional and admirable individuals: playwrights, poets, thinkers, educationalists, visionaries. Figures such as Patrick Pearse were hugely influenced by the revival in Irish culture and literature, which had begun in the mid 19th century. The aftermath of theGreat Famine, the subsequent establishment of the Gaelic League and Gaelic Athletic Association, together with land reform, the downfall of Parnell, the collection of folklore and literature from among the ordinary people in the West of Ireland by figures from an Anglo-Irish background suych as yeats and Lady Gregory: all of these activated and inspired a younger generation of idealists, who were later attracted into the revolutionary movement.

There was some family involvement in the War of Independence on my mother’s side, although I know little detail about the actual involvement. I have a War of Independence service medal, which was awarded to my grandfather. Both my grandparents were very much inspired by the Irish Ireland ideal, as was my mother, who was involved in the Gaelic League, growing up in Mallow in the late 40s and 1950s.

For a long time throughout the 1970s and 1980s, official commemoration of 1916 was discontinued, and indeed discouraged, in the Republic. The Northern Ireland troubles, which began in 1969, frightened the establishment in the South, who feared growing republican paramilitarism in the North and wanted to avoid anything which would appear to “give succour” to such groups, who claimed to be the inheritors of the 1916 vision. Effectively, in doing so,the State ceded its own revolutionary heritage to such groups. For a long time, to even speak of Pearse and the 1916 rising was to lead to accusations of being “a fellow traveller” of the IRA, and epithets such as “hush-puppy Provoism” abounded in the southern media- a term pioneered by the brilliant and gifted polemicist Eoghan Harris. However, to mark the 75th anniversary of the rising in 1991, a small scale military ceremonial was held outside the GPO in Dublin, on the initiative of the then Taoiseach Charles Haughey. A cultural commemoration was organised by a group led by artist Robert Ballagh the following weekend.

For a long time throughout the 1970s and 1980s, official commemoration of 1916 was discontinued, and indeed discouraged, in the Republic. The Northern Ireland troubles, which began in 1969, frightened the establishment in the South, who feared growing republican paramilitarism in the North and wanted to avoid anything which would appear to “give succour” to such groups, who claimed to be the inheritors of the 1916 vision. Effectively, in doing so,the State ceded its own revolutionary heritage to such groups. For a long time, to even speak of Pearse and the 1916 rising was to lead to accusations of being “a fellow traveller” of the IRA, and epithets such as “hush-puppy Provoism” abounded in the southern media- a term pioneered by the brilliant and gifted polemicist Eoghan Harris. However, to mark the 75th anniversary of the rising in 1991, a small scale military ceremonial was held outside the GPO in Dublin, on the initiative of the then Taoiseach Charles Haughey. A cultural commemoration was organised by a group led by artist Robert Ballagh the following weekend.

In late 2005,Taoiseach Bertie Ahern announced at the Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis that his government was going to revive the annual military ceremonial at the GPO. A speech given by President Mary McAleese at UCC in January 2006 (which may be read here) hailed “our idealistic and heroic founding fathers and mothers, our Davids to their Goliaths”. She rather unnecessarily and controversially added “In the nineteenth century an English radical described the occupation of India as a system of ‘outdoor relief’ for the younger sons of the upper classes. The administration of Ireland was not very different, being carried on as a process of continuous conversation around the fire in the Kildare Street Club by past pupils of public schools. It was no way to run a country, even without the glass ceiling for Catholics”. She was roundly abused for this by Kevin Myers in the Irish Times, who slammed her for her “dreadful speech”. Amid some controversy, and notable hostility from certain quarters, a major military parade was organised by the Government, and well publicised in advance. 120,000 people lined the streets of Dublin, and the Irish Times declared in its headline that Ahern’s parade “had won political approval”.

In late 2005,Taoiseach Bertie Ahern announced at the Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis that his government was going to revive the annual military ceremonial at the GPO. A speech given by President Mary McAleese at UCC in January 2006 (which may be read here) hailed “our idealistic and heroic founding fathers and mothers, our Davids to their Goliaths”. She rather unnecessarily and controversially added “In the nineteenth century an English radical described the occupation of India as a system of ‘outdoor relief’ for the younger sons of the upper classes. The administration of Ireland was not very different, being carried on as a process of continuous conversation around the fire in the Kildare Street Club by past pupils of public schools. It was no way to run a country, even without the glass ceiling for Catholics”. She was roundly abused for this by Kevin Myers in the Irish Times, who slammed her for her “dreadful speech”. Amid some controversy, and notable hostility from certain quarters, a major military parade was organised by the Government, and well publicised in advance. 120,000 people lined the streets of Dublin, and the Irish Times declared in its headline that Ahern’s parade “had won political approval”.

In the five years since 2006, the state has continued to hold a military ceremonial at the GPO each Easter Sunday. It is not widely publicised, but is quite an impressive spectacle, with the Minister for Defence, Taoiseach and President arriving on parade. The programme today was fairly typical. The national flag was lowered, a prayer of remembrance was lead by Mgr Eoin Thynne, the Army chaplain, a piper played a lament and an Army officer read the proclamation. An Taoiseach Enda Kenny TD invited President McAleese to lay a wreath in memory of “all those who died”. A minute’s silence was then observed, the Last Post sounded and the national flag raised to full mast. Reveille and the national anthem followed, with Air Corps jets flying overhead. RTE News reported later that 3,000 people had attended the commemoration.

This year, the approaching 95th anniversary of the rising was heralded by a number of newspaper columns, all of them casting a fairly cold eye. It seems true to say that we are deeply conflicted, as a society in the Republic, about 1916 and what it represents. It is indeed odd that the greatest attention which has been paid in over 30 years in the public consciousness to Dublin’s Garden of Remembrance, opened in 1966 to commemorate “all those who died for Irish freedom” has been in the context of the forthcoming visit of Queen Elizabeth II. The Government has apparently secured that the Queen will lay a wreath there, an act of symbolism carefully balanced by plans for her to lay a wreath also at the War Memorial Gardens in Islandbridge, which commemorate the many Irish who served in the regiments of the British Army in the First and Second World Wars. This reflects the carefully balanced commemoration organised by Ahern’s government in 2006, which featured a major military commemoration of the Battle of the Somme at the War Memorial Gardens, and the carrying of Irish regimental flags of the British army (which was then the Irish Army) by officers of the Republic’s defence forces, as well as the Easter Rising commemoration.

It is a difficult path to tread for the Republic’s establishment. There are many within the state whose forefathers were unionist in the 1916 to 22 period, for whom 1916 commemorations are a particularly neuralgic matter. There are the descendants of (Irish)RIC police officers and (Irish) British Army personnel. There are the descendants of some who were burnt out by the (Old) IRA during the War of Independence. There are the descendants of those whose allegiance was to the Irish Parliamentary party, and its leader John Redmond, which were eclipsed in the 1918 general election by Sinn Féin. There are also unionists in the North, who view the 1916 rising and the War of Independence as acts of treachery, particularly egregious because they were committed while Britain was at war-Britain being “stabbed in the back” in their view. Of course,Pearse and his comrades questioned why Britain was exhorting young Irish men to “fight for the freedom of small nations” (notably, Belgium) while Home Rule was being repeatedly long fingered by the British Parliament, in defiance of the wishes of the overwhelming majority in Ireland.

However, many of those not initially sympathetic to the rising, or the politics of its leaders, were moved to pay tribute to their courage and bravery. Prime Minister Asquith in the House of Commons noted that the rebels had mistreated no prisoners of war.

George Russell (AE), the artist, mystic, poet and writer, no sympathiser with the rebels, wrote:

Your dream had left me numb and cold

But yet my spirit rose in pride,

Re-fashioned in burnished gold

The images of those who died,

Or were shut in the penal cell –

Here’s to you, Pearse, your dream, not mine,

But yet the thought – for this you fell –

Turns all life’s water into wine.

In recent years, the southern state, after several decades of official amnesia, has moved to acknowledge the many thousands of Irish who fought and died in the First and Second World Wars. Television documentaries and books have brought their sacrifice to the attention of the public. Over a number of recent years, a rebound hostility to nationalist remembrances has been evident in media and academic commentary. In Ireland, we seem incapable of “both/and” perspectives: it must always be “either/or”. To bolster my sense of belonging and history, yours must be disparaged. The pendulum swings wildly from nationalist triumphalism to aggressively self-critical excoriation. We end up, in the words of a Goverment official in 2006, “almost apologising for our patriot dead”.

But the 1916 rising, the executions which followed, and the War of Independence, did set in train the process which led to independence for the 26 counties. The state cannot realistically wash its hands of the muddied baptismal water from which it took its being. There is much to celebrate and admire in the noble and generous vision of the 1916 proclamation. We are unusual as a country in having no Independence Day. Perhaps when we have the new constitution, promised by Éamon Gilmore during the general election, we can declare Ireland a Republic in our Constitution (we are only a republic by statute at present), and all our citizens can then join in celebrating Republic Day without disowning their complex and diverse pasts.